Following yesterday’s review of El Burrito Express I found this article about a supposed trans-continental burrito shipment tunnel that would deliver a California style burrito to those in Weehauken, NJ in 42 minutes. I had to share this.

Who can imagine New York City without the Mission burrito? Like the Yankees, the Brooklyn Bridge or the bagel, the oversize burritos have become a New York institution. And yet it wasn’t long ago that it was impossible to find a good burrito of any kind in the city. As the 30th anniversary of the Alameda-Weehawken burrito tunnel approaches, it’s worth taking a look at the remarkable sequence of events that takes place between the time we click “deliver” on the burrito.nyc.us.gov website and the moment that our hot El Farolito burrito arrives in the lunchroom with its satisfying pneumatic hiss.

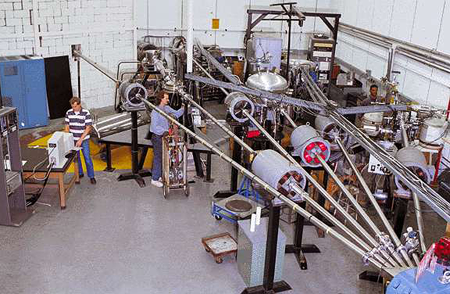

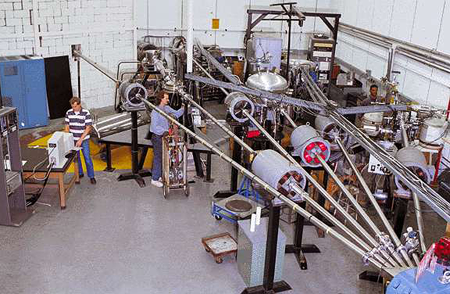

The story begins in any of the three dozen taquerias supplying the Bay Area Feeder Network, an expansive spiderweb of tubes running through San Francisco’s Mission district as far south as the “Burrito Bordeaux” region of Palo Alto and Mountain View. Electronic displays in each taqueria light up in real time with orders placed on the East Coast, and within minutes a fresh burrito has been assembled, rolled in foil, marked and dropped down one of the small vertical tubes that rise like organ pipes in restaurant kitchens throughout the city.

Once in the tubes, it’s a quick dash for the burritos across San Francisco Bay. Propelled by powerful bursts of compressed air, the burritos speed along the same tunnel as the BART commuter train, whose passengers remain oblivious to the hundreds of delicious cylinders whizzing along overhead. Within twelve minutes, even the remotest burrito has arrived at its final destination, the Alameda Transfer Station, where it will be prepared for its transcontinental journey.

Ever since Isaac Newton first described the laws of gravity in 1687, scientists have known that the quickest route between two points is along a straight line through the Earth’s interior. Through the magic of gravity, any object dropped into such a “chord tunnel” at one end will emerge exactly 42 minutes later at the other end, no matter the distance. But for hundreds of years, the technical challenges of building such a tunnel were so daunting that it remained a theoretical curiosity. Only at the start of the 20th century did the idea become technically feasible, and to this day the tunnel linking the East Bay with New Jersey remains the only structure of its kind in the world.

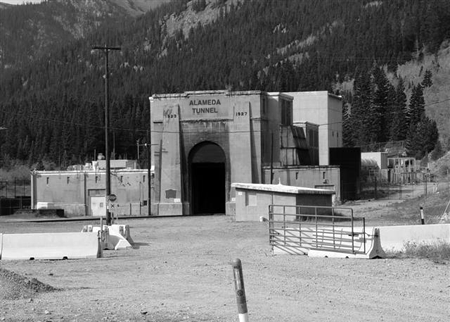

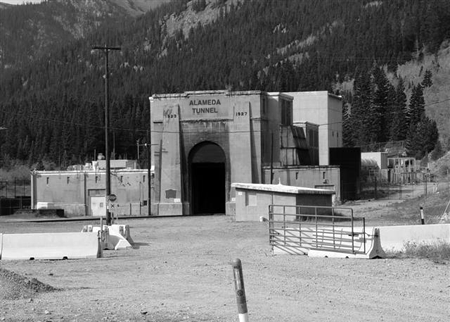

From the outside, the Alameda facility looks like any other industrial building. Behind a chain link razor wire fence sits a windowless white hangar some three stories tall, surrounded by a strip of green lawn. If you could see underground, however, you’d see that the building sits at the center of a converging nexus of burrito pipes. High pressure pneumatic tubes from all over the Bay Area emerge in the center of the facility, spilling silvery burritos onto a high-speed sorting line. The metal-jacketed burritos look like oversize bullets, and the conveyor belts that move them through the facility resemble giant belts of delicious ammunition. Within a few seconds of arrival the burritos have been bar coded, checked for balance and round on a precision lathe, and then flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen.

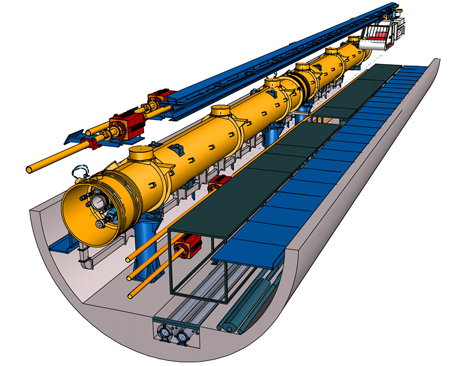

The mouth of the tunnel is a small concrete arch in the side of a nearby hill, about as glamorous as an abandoned railway tunnel. Yet if you could open the airlocks and stare down its length with a telescope, you would see airplanes on final approach to Newark Airport, three thousand miles away! To reduce drag on the burritos to a minimum, the tunnel must be kept in near-vacuum with powerful pumps. At the tunnel’s deepest point the burritos will be traveling nearly two kilometers a second – even the faintest whiff of air would quickly drag them to a stop.

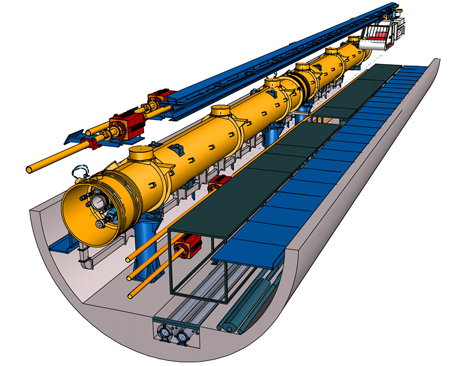

The launch tube for the burritos lies just under the tunnel mouth and looks like what it is: an enormous gun. Every four seconds a ‘slug’ of ten burritos, white with frost, ratchets into the breech. A moment later it flies into the tunnel with a loud hiss of compressed gas, and the lights dim briefly as banks of powerful electromagnets accelerate the burritos to over two hundred miles an hour. By the time they pass Stockton three minutes later the burritos will be traveling faster than the Concorde, floating on an invisible magnetic cushion as they plunge into the lithosphere.

No one who built the Alameda-Weehawken tunnel had quite this future in mind for it. The tunnel had its origins in the early 1900’s as an ambitious project for speeding mail delivery between New York City and the booming Pacific port of San Francisco. The telegraph and railroad had linked the city to the East Coast, but transferring documents, currency, securities and diplomatic correspondence across the country was still a slow affair fraught with danger. In 1911, the celebrated British civil engineer Basil Mott approached the plutocrat Andrew W. Mellon with an audacious plan to build a straight-line tunnel 2500 miles long connecting New York City with San Francisco, allowing packages to be sent between the two cities using only compressed air and gravity. The tunnel would resemble the pneumatic tube systems that had served New York City and Paris so well for mail delivery, but on an incomparably vaster scale. Cylinders containing up to sixteen pounds of mail would be able to make the continental transit in less than an hour.

Construction on the tunnel began in 1913, and it quickly grew into the largest public works project in the young nation’s history. Not until the Eisenhower Interstate system in the 1950’s would there be a bigger or more costly civil engineering project. Drilling the tunnel required over 19 years of continuous effort by thousands of miners, often working in conditions of intolerable confinement and heat. Over 22 million tons of rock had to be removed, much of it from unprecedented depths, all while keeping the tunnel perfectly straight over thousands of miles. Just keeping the tunnels cool required more water each day than flows over Niagara Falls.

The tunnel opened to great fanfare in 1933, with a congratulatory message in Morse Code flashed by powerful searchlight from the San Francisco end to waiting dignitaries on the New Jersey side. It was already obsolete. The first regular mail shipments sent from San Francisco in the spring of 1934 had to compete with the sophisticated air mail system that had grown up during the tunnel’s long construction. To make matters worse, breakdowns in the tunnel were frequent, especially in the central “hot zone” where temperatures could exceed 900 degrees Centigrade. Mail would frequently arrive singed or deformed from the intense heat and pressure. While they could never beat the speed of the tunnel, airplanes could deliver documents at far lower price and risk in just a few dozen hours more. In 1936, at the height of the Depression, the tunnel ceased operation less than three years after it had opened.

In the years to come all kinds of schemes would be floated for how to put the tunnel to use. For a brief time after Pearl Harbor there was serious thought given to using it as an enormous gun barrel that could fire artillery shells across the Pacific at Japan (the risk to life in San Francisco if a charge went off prematurely was deemed too great). In the early days of the Cold War, both ends of the tunnel, along with the Chicago and Cedar Rapids access shafts, were considered as enormous fallout shelters. The low point in the tunnel’s fortunes came with a 1971 proposal (mercifully never enacted) to use the Weehawken side of the tunnel as the world’s deepest garbage chute. On the San Francisco end, meanwhile, squatters from the thriving San Francisco countercultural scene had begun using the tunnel as an easy place to take shelter.

By the early 1970’s the tunnel was a derelict, a mostly forgotten relic of a more adventurous time. The turning point came when Robert Cavanaugh, a New York financier with a serious taste for Mexican food, happened to come across a mention of the tunnel in a zoning proposal. The globetrotting Cavanaugh was a fanatic of the recently-invented Mission burrito but bemoaned being unable to get it anywhere outside of San Francisco. Examining blueprints of the defunct mail tunnel on a flight home to New York, Cavanaugh became intrigued by the coincidence in size between a foil-wrapped burrito and the diameter of the old transcontinental mail tubes. By the time the plane landed, he had come up with an audacious plan.

Cavanaugh realized that the intense heat of the transit that had so beleaguered mail service would actually work to his advantage in a burrito tunnel. The burritos could be stored frozen on the Western end and arrive fully heated through in New Jersey. Furthermore, advances in electrical engineering meant that containers would no longer have to be propelled by compressed gas. The burritos already came conveniently wrapped in aluminum foil – it would be trivial to accelerate them with powerful magnets.

Encouraged by his back-of-the-envelope calculations, Cavanaugh formed a consortium and, in a stroke of genius, convinced the Carter Administration to subsidize the tunnel’s operation in exchange for access to the geothermal heat it would produce. Convincing skeptical businessmen to buy into the plan proved more of a challenge – it took six months to persuade suspicious taqueria owners to switch to a salsa with lower magnetic permittivity. Finally, in July of 1979, all the pieces were in place. After a successful July 2 dry run with a sawdust mock burrito, the tunnel ceremoniously opened on Independence Day. The inaugural burrito (carnitas with lettuce, salsa and avocado, no beans) was loaded into the breech at the Alameda terminus at 10:05 AM and was served to a beaming Cavanaugh, Vice President Walter Mondale and New York mayor Ed Koch in Weehawken 64 minutes later. Two hundred burritos followed that same day; by the end of the decade the tunnel would be delivering over two thousand burritos an hour.

In the early days of the burrito tunnel workers on the Alameda side would sometimes use it to send small packages or letters, inking the code words sin carne on the wrapper to alert those on the other end that the ’burrito’ required special handling. This changed after September 11, when strict security measures went into force. Homeland Security officials have been quick to recognize the unique threat of a tunnel that could give terrorists unimpeded access to the entire underside of the nation. They’ve also been alert to the danger a “dirty burrito” could pose if it made it into the New York food supply. Director of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff would not comment on specific measures his department has taken to protect the tunnel, but he said his office does take the potential threat very seriously. “We’ve known since the first World Trade Center bombing that New York is a top target. We’re taking appropriate measures to make sure the tunnel and the burritos that pass through it remain safe and secure.”

The greatest risks to the tunnel, however, are likely to come from Mother Nature herself. During the 1989 Loma Prieta quake the tube misaligned by over four inches, requiring extensive redrilling, and experts estimate that an earthquake of magnitude 6 or greater on the Hayward Fault could put it out of commission for months. An ambitious expansion plan to begin next year will address some of the seismic hazards while also widening it enough to allow super burritos to make the transit for the first time ever.

Burritos speeding through the tunnel fight a constant battle against friction. At the start and end of their journey they hover in a powerful magnetic field, seldom touching the sides of the tunnel. Past the Colorado border, however, the temperature of the surrounding rock exceeds the Curie point of iron and the burritos must slide on their bellies in their nearly frictionless Teflon sleeve, kept from charring by pork fat that slowly seeps out of the burritos as they thaw. By the time the burritos reach Cedar Rapids (traveling well over a mile a second) they are heated through, and anyone who managed to penetrate into the tunnel through the Cleveland access shafts would find them ready to eat.

Remarkably, people do descend into even the deepest sections of the tunnel, though with a far more serious goal in mind than lunch. Geologists from around the globe have been flocking to the tunnel for five decades. “People in our profession get excited about new road cuts,” says Adam Rifkin, Dean of the Geology Department at the University of Nebraska. “You can imagine what it’s been like for us to explore the world’s deepest tunnel.” Indeed, the Alameda tunnel is the only place in the world where scientists can directly study the aesthenosphere, the boundary layer separating the earth’s crust from the hot mantle. The trip down through the access shafts is harrowing – the descent takes the better part of a day, and temperatures can rise to nearly a thousand degrees Centigrade. Most of the work at the depth of the tunnel is done by robots, but geologists must occasionally descend in person to make repairs or to do work that is too difficult to automate. “It’s a lot like standing in an oven,” Rifkin says. “At the lowest point we’re nearly as far from the surface as the Space Shuttle, and in many ways it’s a less forgiving environment.” Still, he adds, “I wouldn’t give it up for the world. This is probably one of the dullest places, geologically speaking, in the whole country. Under our feet are five miles of silt from the Rockies before you even get to the first rock. Thanks to the tunnel, though, we can punch right through that. It’s like a time machine through the planet’s history.”

“Are you ever tempted to sneak a burrito while down there?” I ask Dr. Rifkin, and he laughs. “At the speed those things are going it would probably take your hand off. But really for us this is serious business – we’re fine not having access to great Mexican food as long as we can do the geology. The tunnel has been an absolute godsend.”

Not everyone is as delighted with the tunnel as the geologists. Old-time San Franciscans will be quick to point out that the comestibles in the tunnel flow strictly one way. “In the old days you’d go to a place like Pancho Villa and get yourself a steak burrito in five minutes, maybe ten if it was near lunchtime,” says lifelong Mission resident Howard Washington. “Now the line is out the door even in the morning. And some of those places down in the South Bay won’t even take customers anymore. If you want a burrito in the daytime you have to get it first thing, or else you go to one of the places that isn’t hooked up to the tunnel.”

Taqueria owners have tried hard to cope with the additional demand, but even they admit that it can get hectic. “The New York metro area has fifteen million people,” explains Javier Corrientes, manager of Cancun Burrito on Valencia Street. “San Francisco is barely a tenth of that size. You got all those people out drinking on a Friday night who want a burrito at ten o’clock, just when the dinner rush is starting here, there’s no way we can keep up.” The secret, he says, is to order tacos. “It’s the same fillings, except it’s quicker to put together and you can’t put it through the tunnel.”

The raw economics of the burrito trade suggest San Franciscans won’t be getting quicker service any time soon. Even before tolls and taxes, a burrito sold in New York brings in ten times the profit of one sold over the counter. John Laplace chairs the Northern California Burrito and Burro Council, an industry group representing Bay Area taquerias. “The tunnel is an incredible economic engine for the region,” he says. “Every burrito that goes through the tunnel represents over two dollars in direct tax revenue and over four dollars in indirect revenue through job creation, research stimulus and geothermal energy. I can understand why people get frustrated, but that tunnel has given us far more than it’s taken.”

Of course, it would be best if the tunnel could give back in a more tangible way. Over the years there have been numerous attempts to send New York staples in the reverse direction – operators have tried sending knishes, bagels, pickles and even Brooklyn-style pizza. None have proven as resilient as the humble burrito, and in the end the two cities have bowed to the inevitable. Both tunnel tubes now carry only burritos.

By the time they reach Cleveland the burritos are fully heated through and traveling uphill at about twice the speed of sound. A series of induction coils spaced through central Pennsylvania repeats the magnetic process in reverse, draining momentum from the burritos and turning it into electrical power (though Weehawken residents still recall the great blackout of 2002, when computers running the braking coils shut down and for four hours burritos traced graceful arcs into the East River, glowing like faint red sparks in the night).

At the tunnel exit, a final puff of air slows the burritos to a stop and they are placed in insulated bags. These are whisked to a fleet of waiting trucks, which pass through the Holland Tunnel (this time at a more stately thirty-five miles per hour) and then onward to restaurants and cafeterias throughout the five boroughs.

Is it worth it? Enrique Alnazar, burrito sommelier for Nobu Fifty-Seven, smiles at the very question. The restaurant recently installed a dedicated high-speed pneumatic line to the Weehawken facility, shortening the arrival time for its prize Los Charros burritos from just over two hours to under fifty minutes. Alnazar won’t say how much the new line cost (estimates run into the millions of dollars), but he insists it was worth every penny. “We’ve had people come in and order a magnum of 1978 Château Margaux on the strength of our burritos. They know that we’re phoning in their order to Mountain View the moment they walk in the door, and they know we’ve done everything in our power to keep them from waiting. A lot of restaurants are happy racking up a few days’ supply in the burrito cellar, but that’s not the same as getting a fresh burrito straight from the tunnel – you can taste the difference. The only way to get a fresher burrito than at Nobu is to fly to California, and our customers appreciate that.”

The success of the burrito tunnel has encouraged no end of imitators – whether the Reagan-era attempt to construct an intracoastal barbeque pipeline, the perennial political deadlock over allowing tomatoes in the Northeastern Chowder Viaduct, or the recent fiasco of high-speed BagelRail. But as Chairman Laplace argues, it’s unlikely such a project could succeed anywhere else. “We really have a unique situation here – a population of fifteen million people without access to high-quality Mexican food. There’s no place else in the country like it, and that makes the economics of a transport tunnel from the country’s finest burrito region workable. On top of this you have the burrito itself, which is a really marvelous food — resilient to overheating, isotropic, compact, able to tolerate high G forces.” Here Laplace smiles. “And delicious. Who would want to live in a New York City without it?”

The following is from idlewords.com. I cannot verify the authenticity of this article, nor who the author was, but it was just so damn funny I had to repost it.

[ad#AdBrite]

I know, that statement is sacrilege and should never be uttered in San Francisco, but I have been noticing a new trend where people are moving away from their first love of burritos and trying tacos again. Not the Taco Bell style fast food garbage, but real, California Style Tacos.

I know, that statement is sacrilege and should never be uttered in San Francisco, but I have been noticing a new trend where people are moving away from their first love of burritos and trying tacos again. Not the Taco Bell style fast food garbage, but real, California Style Tacos. Enter the taco. I have a couple of taquerias I frequent and know the people who work there and asked them, How come you don’t make a pequeño, but you make a super? Every time the answer was the same…If you want pequeño order a taco!

Enter the taco. I have a couple of taquerias I frequent and know the people who work there and asked them, How come you don’t make a pequeño, but you make a super? Every time the answer was the same…If you want pequeño order a taco!